To Read #4

In Praise of Mediocrity

The pursuit of excellence has infiltrated and corrupted the world of leisure.

By Tim Wu

Izhar Cohen

I’m a little surprised by how many people tell me they have no hobbies. It may seem a small thing, but — at the risk of sounding grandiose — I see it as a sign of a civilization in decline. The idea of leisure, after all, is a hard-won achievement; it presupposes that we have overcome the exigencies of brute survival. Yet here in the United States, the wealthiest country in history, we seem to have forgotten the importance of doing things solely because we enjoy them.

Yes, I know: We are all so very busy. Between work and family and social obligations, where are we supposed to find the time?

But there’s a deeper reason, I’ve come to think, that so many people don’t have hobbies: We’re afraid of being bad at them. Or rather, we are intimidated by the expectation — itself a hallmark of our intensely public, performative age — that we must actually be skilled at what we do in our free time. Our “hobbies,” if that’s even the word for them anymore, have become too serious, too demanding, too much an occasion to become anxious about whether you are really the person you claim to be.

If you’re a jogger, it is no longer enough to cruise around the block; you’re training for the next marathon. If you’re a painter, you are no longer passing a pleasant afternoon, just you, your watercolors and your water lilies; you are trying to land a gallery show or at least garner a respectable social media following. When your identity is linked to your hobby — you’re a yogi, a surfer, a rock climber — you’d better be good at it, or else who are you?

Lost here is the gentle pursuit of a modest competence, the doing of something just because you enjoy it, not because you are good at it. Hobbies, let me remind you, are supposed to be something different from work. But alien values like “the pursuit of excellence” have crept into and corrupted what was once the realm of leisure, leaving little room for the true amateur. The population of our country now seems divided between the semipro hobbyists (some as devoted as Olympic athletes) and those who retreat into the passive, screeny leisure that is the signature of our technological moment.

I don’t deny that you can derive a lot of meaning from pursuing an activity at the highest level. I would never begrudge someone a lifetime devotion to a passion or an inborn talent. There are depths of experience that come with mastery. But there is also a real and pure joy, a sweet, childlike delight, that comes from just learning and trying to get better. Looking back, you will find that the best years of, say, scuba-diving or doing carpentry were those you spent on the learning curve, when there was exaltation in the mere act of doing.

In a way that we rarely appreciate, the demands of excellence are at war with what we call freedom. For to permit yourself to do only that which you are good at is to be trapped in a cage whose bars are not steel but self-judgment. Especially when it comes to physical pursuits, but also with many other endeavors, most of us will be truly excellent only at whatever we started doing in our teens. What if you decide in your 40s, as I have, that you want to learn to surf? What if you decide in your 60s that you want to learn to speak Italian? The expectation of excellence can be stultifying.

Liberty and equality are supposed to make possible the pursuit of happiness. It would be unfortunate if we were to protect the means only to neglect the end. A democracy, when it is working correctly, allows men and women to develop into free people; but it falls to us as individuals to use that opportunity to find purpose, joy and contentment.

Lest this sound suspiciously like an elaborate plea for people to take more time off from work — well, yes. Though I’d like to put the suggestion more grandly: The promise of our civilization, the point of all our labor and technological progress, is to free us from the struggle for survival and to make room for higher pursuits. But demanding excellence in all that we do can undermine that; it can threaten and even destroy freedom. It steals from us one of life’s greatest rewards — the simple pleasure of doing something you merely, but truly, enjoy.

Tim Wu (@superwuster) is a law professor at Columbia, the author of “The Attention Merchants: The Epic Struggle to Get Inside Our Heads” and a contributing opinion writer.

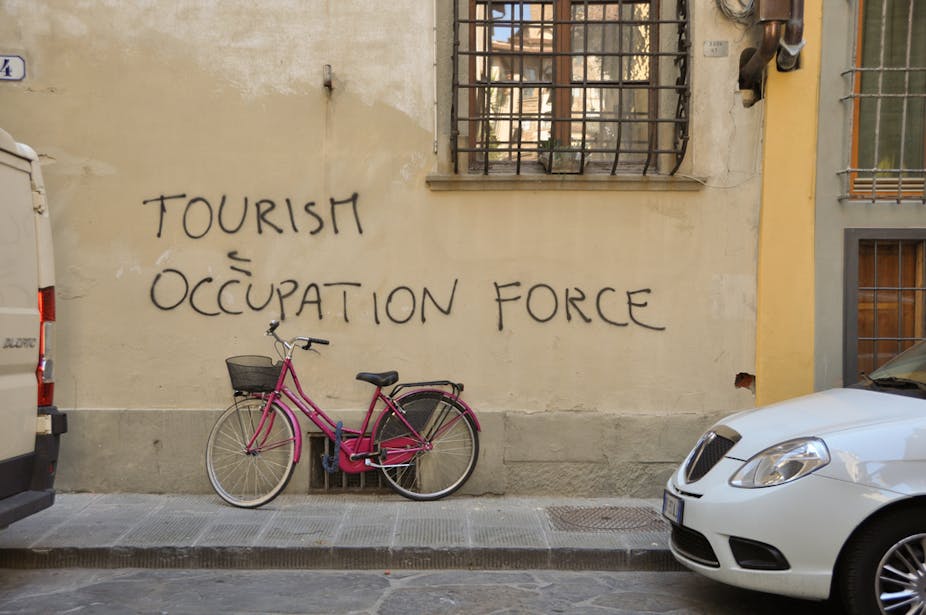

Kyoto: beautiful view, shame about the crowds. Shutterstock

Kyoto: beautiful view, shame about the crowds. Shutterstock